The past year proved to be a remarkable one for the field of archaeology. Advancements in techniques, particularly the use of AI, have facilitated significant breakthroughs, while researchers have also offered fresh insights into artifacts discovered in earlier excavations. Moreover, it has been a year rich in new archaeological revelations, such as the discovery of mummification workshops in Egypt that unveil some mysteries surrounding ancient burial practices; a submerged temple in Italy constructed 2,000 years ago by traders from the Arabian deserts; and a vast Maya city hidden beneath jungle foliage that was uncovered using laser technology. Here are seven of the most intriguing recent finds:

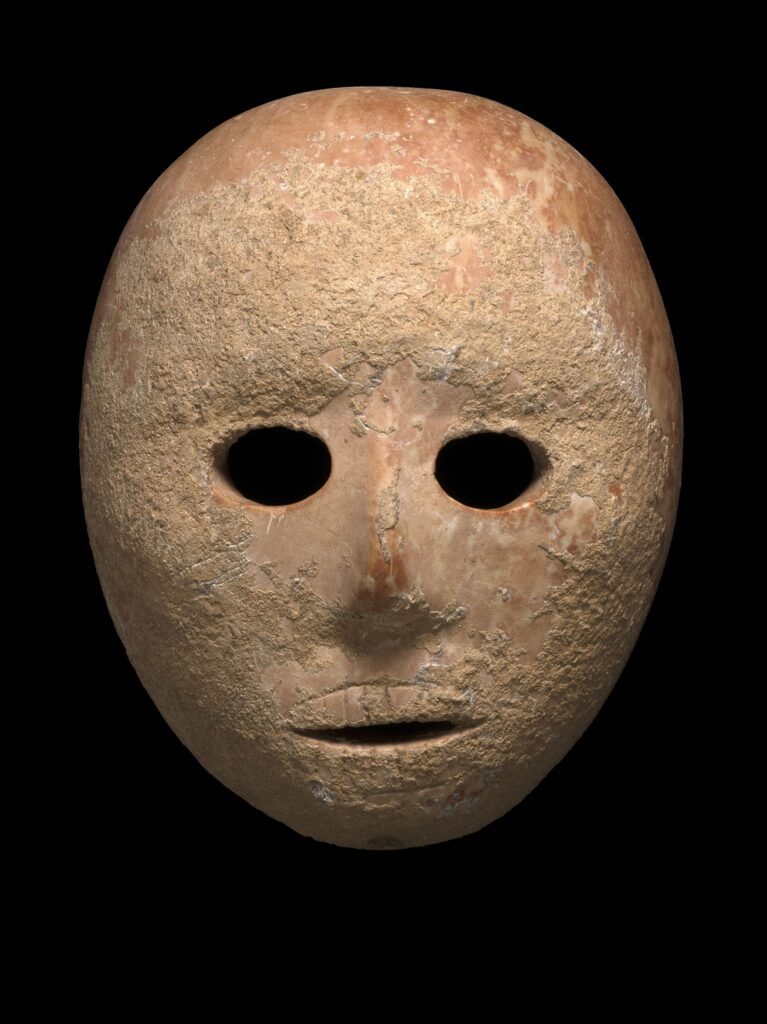

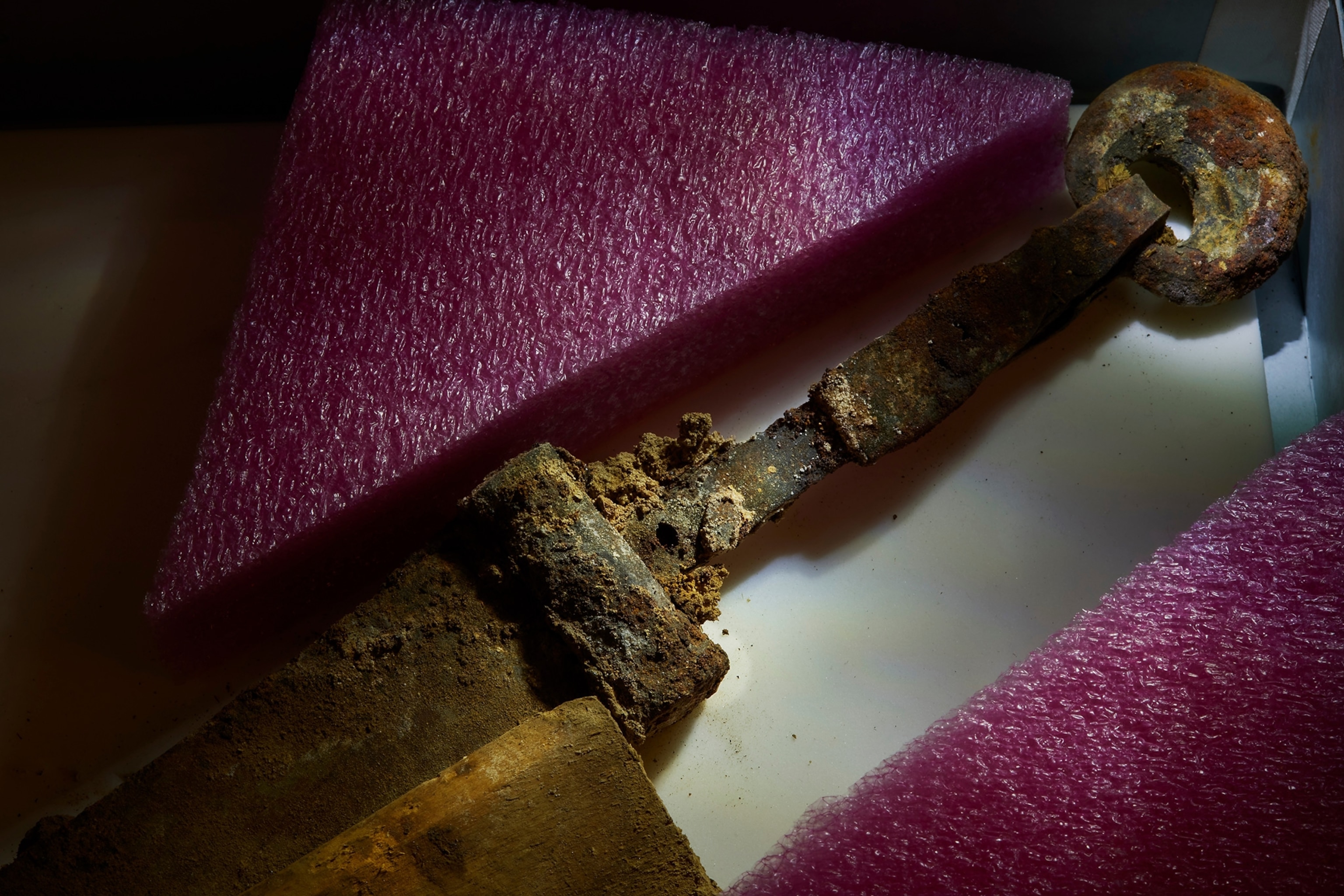

Swords from the Dead Sea

Eitan Klein, director of the Israel Antiquities Authority’s Judean Desert Survey Project and deputy director of the Antiquities Looting Prevention Unit, inspects an iron pilum (javelin) head discovered in a cave southeast of Jerusalem. The unearthing of this javelin led researchers to four exceptionally well-preserved swords that had been lodged behind stalactites within the cave. Weapons like this ring-pommel sword were favored by Rome’s adversaries before being adopted by the Empire in the 2nd century A.D. In June, archaeologists discovered these four swords, which date back to between the first and third centuries A.D., during a period when the area served as a sanctuary for Jewish rebels opposing Roman rule. Normally, wood and leather would decompose quickly, but the dry conditions of the cave preserved these items, allowing for complete swords with their hilts and scabbards to be recovered. The initial discovery of the iron point of a Roman javelin and pieces of worked wood prompted a thorough search of the cave with metal detectors, which ultimately uncovered the four swords. It is believed that these weapons were likely hidden by Jewish rebels during the Bar Kokhba revolt, which occurred between A.D. 132 and 136, after they had salvaged them from battlefields or stolen them from Roman forces. Archaeologists are particularly excited about the preservation of wood and leather, which may assist in determining when and where the swords were produced.

A Newly Discovered Giant Stone Head on Rapa Nui

In February, volunteers uncovered a newly found giant stone head known as a moai on Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, situated over 2,000 miles off the coast of Chile. This particular statue is relatively small for a moai, measuring just over five feet tall, whereas many of the approximately 900 moai on the island reach heights of up to 33 feet (with one unfinished moai estimated to exceed 70 feet upon completion). Discovered in a desiccated crater lake, archaeologists suspect there may be additional finds awaiting discovery in the area. Most moai were constructed between 1250 and 1500, and local inhabitants regard these statues as the “living faces” of their revered ancestors. While little is known about this latest moai, including its ancestral representation, archaeologists plan to search for tools used to carve it from soft volcanic rock. Additionally, wooden tablets inscribed with glyphs known as rongorongo may provide further insights—if they can be deciphered.

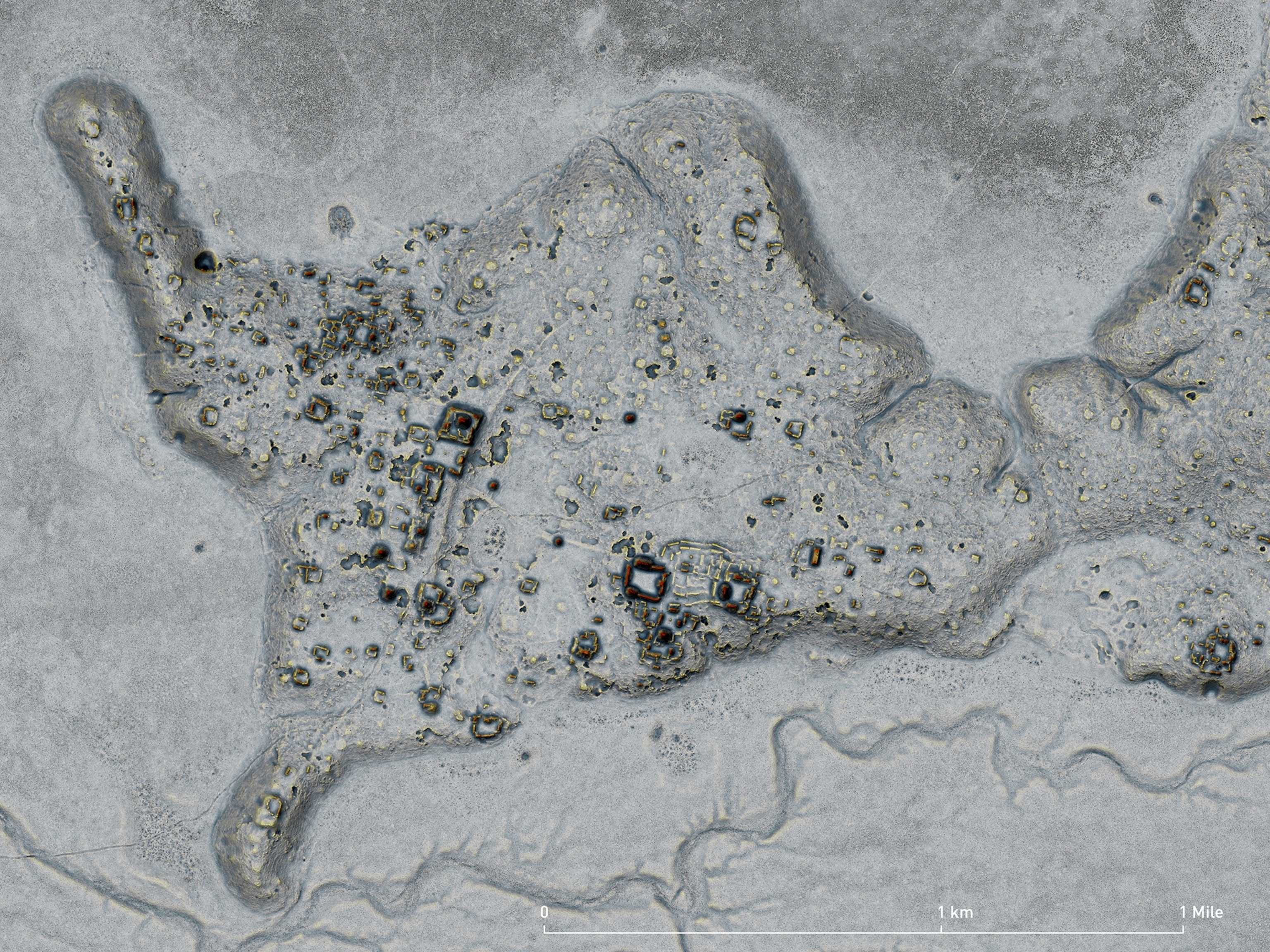

Lost Maya City Revealed via Lidar

No longer lost: Archaeologists unveiled the ancient Maya city of Ocomtún this year through the application of lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) technology, illustrated here in a data visualization. Experts believe this 120-acre city would have been a significant center of civilization. The transformative capabilities of lidar were showcased in June with the identification of this previously unknown Maya city on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. This technology employs airborne equipment to scan the terrain below with thousands of laser pulses each second, unveiling features obscured by trees and other natural cover—similar to revealing historical bends and channels of the Mississippi River or military shelters from World War II. Those who explored the site on foot have named it “Ocomtún,” derived from the Yucatec Maya term for its numerous stone columns. Scholars estimate that it thrived from around A.D. 250 until its abandonment during the collapse of Maya civilization between 900 and 1000, possibly due to drought and internal conflict. Ocomtún spans over 120 acres and showcases plazas, ball courts, elite residences, raised platforms, ritual altars, and pyramid temples; notably, the remnants of its largest pyramid stand at over 80 feet tall.

An Underwater Temple in Italy

An archaeologist clears away sediment from a white marble altar found submerged in waters near Puteoli, Italy. This altar belongs to an ancient temple attributed to the Nabataeans—desert merchants whose immense wealth led to the establishment of cities like Petra in Jordan. In August, Italian archaeologists announced their discovery near Naples of this underwater temple built approximately 2,000 years ago by ancient Nabateans. Originating from present-day Jordan and Saudi Arabia, these merchants also founded Petra and supplied Romans with Eastern luxuries. Much of their trade reached the port of Puteoli (now Pozzuoli), located a few miles west of Naples; volcanic activity submerged the temple along the port’s coastline while remaining visible from Mt. Vesuvius. The underwater ruins include an altar dedicated to Nabatean deities; researchers suggest that this temple acted as both a “billboard” for Nabatean culture and a site for worship. A Latin inscription on a piece of marble narrates that “Zaidu and Abdelge offered two camels to [the god] Dushara,” possibly as a sacrifice aimed at securing favorable trade negotiations or seeking blessings for perilous sea voyages.

Two Mummification Workshops Unearthed in Egypt

In May, Egyptian archaeologists revealed their discovery of two additional mummification workshops located at the Saqqara necropolis near the remnants of ancient Memphis, just south of Cairo. These workshops date back to the 30th dynasty (380 to 345 B.C.) and the Ptolemaic period (305 to 30 B.C.), marking a later phase in ancient Egyptian history; the practice of mummification for preserving bodies for the afterlife has origins dating back to around 2600 B.C. One workshop features stone beds intended for human body preparations, while another contains smaller beds thought to be used for mummifying animals. Researchers uncovered mummification tools, clay jars for storing entrails, ritual vessels for embalmed organs, as well as supplies of natron—a type of soda ash sourced from arid lake beds that played a vital role in the embalming process.

Gemstones Discovered at a Roman Bathhouse

Archaeologists announced in June their finding of numerous gemstones at an ancient Roman bathhouse site in Carlisle, England. Among these artifacts are representations of Roman deities and animals carved into various stones. These discoveries were made amid ruins of an old drainage system designed to carry water away from public baths dating back to the third and fourth centuries. It is believed that these gemstones were once part of jewelry worn by affluent bathers but fell into drains as their settings loosened due to humidity and heat. The collection includes semiprecious stones like agate, jasper, amethyst, and carnelian; some feature depictions of Roman gods such as Apollo, Venus, and Mars, while others portray animals like rabbits and birds. These carved gemstones—known as intaglios—were utilized by Romans as signature seals pressed into clay or wax. The ancient drainage system was located beneath a pavilion associated with the Carlisle Cricket Club; during Roman Britain, this area was recognized as Luguvalium.

A Wartime Shipwreck in the South China Sea

In April, Australian search teams announced their discovery of the wreckage belonging to the Montevideo Maru, a Japanese transport ship that sank in 1942 while carrying over a thousand Allied prisoners-of-war. This ship was transporting Australian troops captured during Japan’s invasion of New Guinea alongside Norwegian sailors and more than 200 civilians who had also been taken captive. The vessel was en route to Hainan Island in China—which was under Japanese occupation—when it was detected by the American submarine U.S.S. Sturgeon off the northern coast of the Philippines. Unaware that Allied POWs were aboard, the Sturgeon tracked and ultimately sank the ship with torpedoes after several hours. Tragically, none of the prisoners survived this event—the largest maritime disaster in Australia’s history—though some Japanese crew members did manage to survive and reported that some prisoners who had escaped onto makeshift rafts sang “Auld Lang Syne” in tribute to their fallen comrades still trapped aboard the sunken vessel.