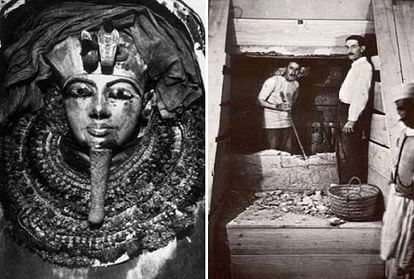

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 was a monumental event that captivated the world and provided unparalleled insights into the life and times of the young pharaoh who ruled ancient Egypt over 3,000 years ago. Among the countless artifacts and treasures found within the tomb, two funereal wreaths of dry, preserved flowers have become the subject of intense fascination and scholarly investigation.

Recent analysis by experts has revealed that nearly half of the flower species used in the construction of these wreaths appear to be of non-Egyptian origin, hinting at the existence of expansive trade networks and cultural exchanges that flourished during Tutankhamun’s reign. In this blog post, we will delve into the significance of these floral discoveries, exploring what they can tell us about the ancient world and the interconnected civilizations that thrived in the Nile Valley and beyond.

The Discovery of Tutankhamun’s Floral Wreaths

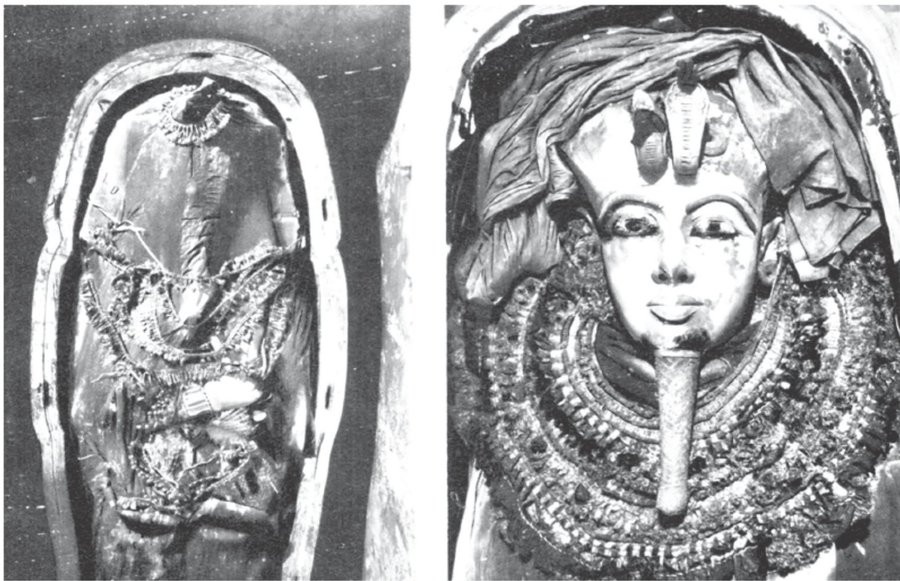

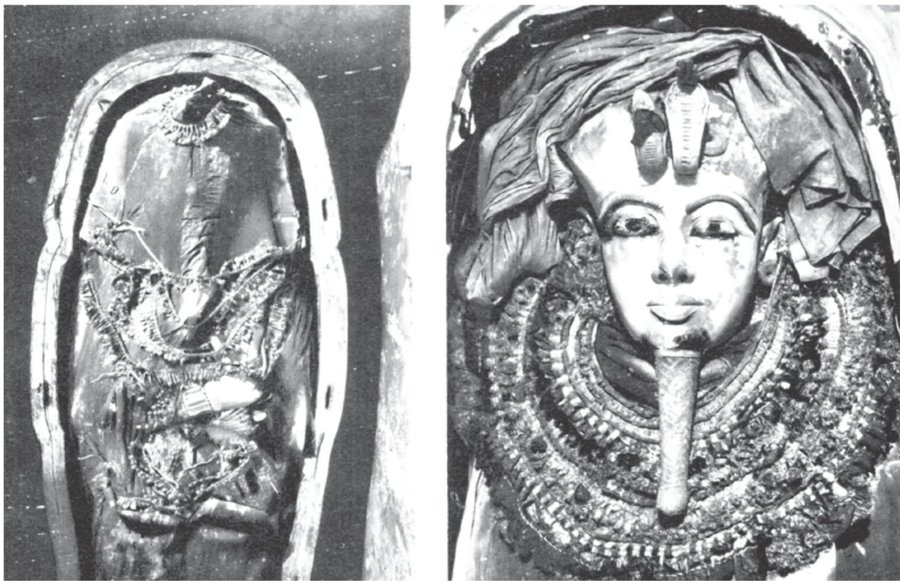

When Howard Carter and his team first entered the intact tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, they were greeted by an astounding array of artifacts and treasures that shed light on the life and death of the young pharaoh. Among the most intriguing discoveries were the two floral wreaths found resting on the lid of Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus.

The first wreath, placed on the king’s head, was composed of hundreds of delicate flowers, carefully woven together to create a stunning funereal crown. The second wreath, found at the foot of the sarcophagus, was equally intricate, showcasing a diverse array of blooms in a variety of colors and shapes.

Initial analysis of the wreaths revealed that they were made up of a wide range of flower species, some of which were immediately recognizable as native to the Nile Valley region, such as the vibrant blue lotus and the fragrant Egyptian blue water lily. However, what truly piqued the interest of archaeologists and botanists were the numerous species that appeared to be of non-Egyptian origin, hinting at the existence of extensive trade networks and cultural exchanges during Tutankhamun’s time.

Uncovering the Origins of the Floral Wreaths

In the decades following the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, researchers have meticulously studied the floral wreaths, employing advanced scientific techniques to identify the various plant species and trace their geographical origins. This painstaking work has yielded a wealth of insights into the ancient world and the interconnected civilizations that thrived during the 18th Dynasty of ancient Egypt.

The Egyptian Flowers

Among the more readily identifiable flowers found in the wreaths were several species native to the Nile Valley region, including:

- Blue Lotus (Nymphaea caerulea): A sacred aquatic plant that was deeply revered in ancient Egyptian culture, often associated with the sun god Ra and used in religious ceremonies.

- Egyptian Blue Water Lily (Nymphaea caerulea): Another aquatic plant that was highly prized for its beautiful blue flowers and symbolic significance in ancient Egyptian mythology.

- Papyrus (Cyperus papyrus): A tall, reed-like plant that was ubiquitous along the Nile River and used for a variety of purposes, from boat-making to the production of the famous papyrus scrolls.

- Cornflower (Centaurea depressa): A vibrant blue flower that was likely cultivated in ancient Egyptian gardens and used to adorn religious offerings and funerary objects.

The presence of these distinctly Egyptian plant species in the wreaths underscores the deep cultural and religious significance that flowers held in Tutankhamun’s world, serving as symbols of rebirth, fertility, and the eternal cycle of life and death.

The Non-Egyptian Flowers

However, it is the non-native flowers found in the wreaths that have truly captivated the imagination of scholars and the public alike. Through painstaking botanical analysis, researchers have been able to identify a number of plant species that originated from distant lands, hinting at the existence of extensive trade networks and cultural exchanges that flourished during Tutankhamun’s reign.

Some of the more intriguing non-Egyptian flowers found in the wreaths include:

- Frankincense (Boswellia sp.): A fragrant resin derived from trees native to the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa, used extensively in ancient Egyptian religious rituals and as a valuable trade commodity.

- Myrrh (Commiphora sp.): Another aromatic resin, this one originating from trees in the Horn of Africa, that was highly prized in the ancient world for its medicinal and religious properties.

- Caper (Capparis sp.): A flowering shrub native to the Mediterranean region, the caper flowers found in the wreaths suggest the existence of trade routes linking ancient Egypt to the broader Mediterranean world.

- Olive (Olea europaea): The presence of olive leaves in the wreaths indicates the importation of this valuable crop from the Levant, where olive cultivation was well-established during the Bronze Age.

The discovery of these non-native flowers in Tutankhamun’s funerary wreaths has led scholars to conclude that ancient Egypt maintained extensive trade networks and cultural exchanges with civilizations throughout the ancient Near East and Mediterranean world. These findings challenge the long-held notion of ancient Egypt as an isolated, insular society, instead revealing a vibrant, interconnected world where the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural influences was the norm.

Implications for Understanding Ancient Trade and Cultural Exchange

The floral discoveries within Tutankhamun’s tomb have far-reaching implications for our understanding of the ancient world and the complex web of trade and cultural exchange that existed during the 18th Dynasty of ancient Egypt. By shedding light on the diverse range of plant species used in the construction of the funereal wreaths, researchers have been able to piece together a more nuanced and comprehensive picture of the global connections that defined Tutankhamun’s era.

Expanding the Boundaries of the Ancient Near East

One of the most significant insights gleaned from the floral wreaths is the evidence they provide for the expansive reach of ancient Egyptian trade networks. The presence of frankincense and myrrh, both of which originate from the Horn of Africa, suggests that the Nile Valley civilization maintained robust commercial and cultural ties with the societies of the Arabian Peninsula and the Red Sea region.

Similarly, the discovery of olive leaves in the wreaths points to the existence of trade routes linking ancient Egypt to the Levant, where olive cultivation was a well-established practice during the Bronze Age. This finding challenges the traditional view of ancient Egypt as an insular, self-contained civilization, instead revealing it as a dynamic, outward-looking society that was deeply integrated into the broader economic and cultural fabric of the ancient Near East.

Tracing the Diffusion of Plant Species and Agricultural Practices

The floral wreaths found in Tutankhamun’s tomb also offer valuable insights into the diffusion of plant species and agricultural practices throughout the ancient world. The presence of non-native flowers, such as the caper and the olive, suggests that the exchange of crops, horticultural techniques, and botanical knowledge was a common occurrence during this period.

This diffusion of plant species and agricultural practices likely played a crucial role in shaping the cultural and culinary traditions of the ancient Near East and Mediterranean civilizations. As trade networks expanded and cultural exchanges intensified, the introduction of new crops and horticultural techniques would have had a profound impact on local economies, diets, and even religious practices.

Insights into Ancient Egyptian Religion and Funerary Customs

In addition to the insights they provide into ancient trade and cultural exchange, the floral wreaths found in Tutankhamun’s tomb also offer valuable clues about the religious and funerary customs of ancient Egypt. The careful selection and arrangement of the flowers, which included both native and non-native species, suggests that the construction of these wreaths was a highly ritualized and symbolically significant process.

The presence of sacred plants like the blue lotus and the Egyptian blue water lily underscores the deep spiritual and mythological significance that flowers held in ancient Egyptian culture. These plants were often associated with deities, religious rituals, and the cycle of life and death, making them essential elements of Tutankhamun’s funerary rites and his journey to the afterlife.

Conclusion: Unlocking the Secrets of the Past

The floral wreaths discovered in the tomb of Tutankhamun have captivated the imagination of scholars and the public alike, serving as a powerful reminder of the rich cultural heritage and global interconnectedness that defined the ancient world. Through the painstaking analysis of these delicate botanical remains, researchers have been able to uncover a wealth of insights into the trade networks, agricultural practices, and religious customs that flourished during the 18th Dynasty of ancient Egypt.

As we continue to explore and interpret the artifacts and treasures found within Tutankhamun’s tomb, the floral wreaths stand as a testament to the enduring power of the past to shape our understanding of the present. By unlocking the secrets contained within these fragile botanical remains, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and dynamism of the ancient world, and the vital role that cultural exchange and global connectivity have played in shaping the course of human civilization.