Overview of Research

Archaeologist Joanna Ostapkowicz from the University of Oxford has been diligently exploring the extensive collection at the National Anthropological Archives (NAA) of the Smithsonian Institution. She highlights the archive as an invaluable resource containing documents from influential researchers in archaeology and anthropology. The records include significant surveys from the Bureau of American Ethnology in the nineteenth century and excavations by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s. Ostapkowicz focuses her research on pre-Columbian Caribbean wooden sculptures and recently discovered an important manuscript related to a unique artifact known as a cemí, crafted by the Indigenous Taíno people.

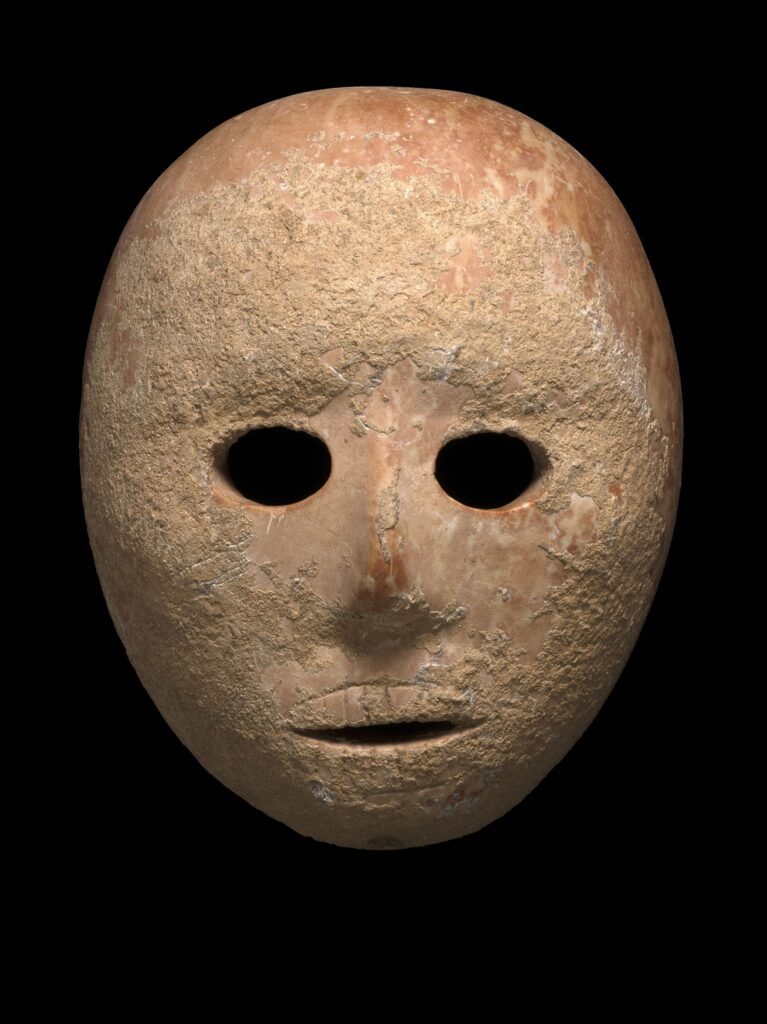

Significance of the Cemí

The cemí is a two-foot-tall cotton figure that represents a divine or ancestral spirit and is the only known surviving example collected by European explorers between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is believed to have originated in the Maniel region of southern Dominican Republic and includes parts of a human skull. Ethnographic accounts suggest that the Taíno used cemís as oracles, which may explain the artifact’s animated appearance.

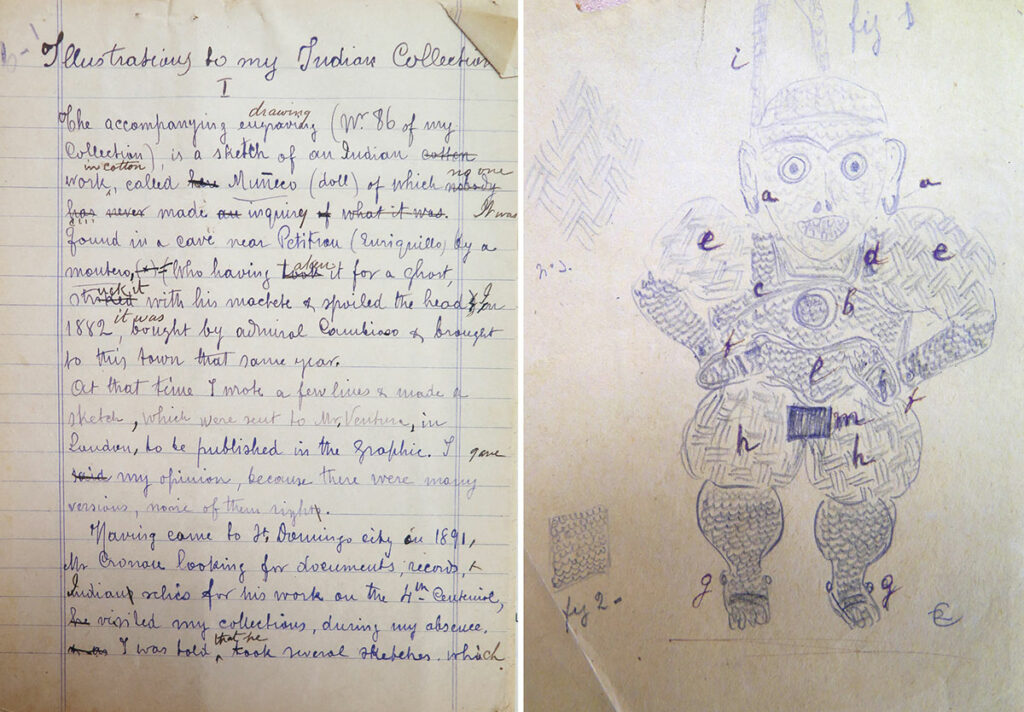

Discovery of the Manuscript

The manuscript Ostapkowicz found is an eight-page description of the cemí written in English by Dominican journalist Rodolfo D. Cambiaso in 1907. His father acquired the artifact in 1882, and the manuscript clarifies its origins, stating it was discovered in a cave near Petitrou (now Enriquillo). This detail has significantly altered how archaeologists understand the cemí’s history by linking it to local archaeological sites and cacicazgos.

Current Research and Findings

The cemí is housed at the University of Turin’s Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, where Ostapkowicz and anthropologist Cecilia Pennacini have conducted noninvasive analyses, revealing its internal structure. They radiocarbon dated it to between 1441 and 1522, which corresponds with the time shortly before or after European contact. Earlier theories suggested it was made later by escaped enslaved Africans.

Importance of Archival Research

Ostapkowicz emphasizes that this discovery illustrates the crucial role of historical records in understanding artifacts from before modern scientific methods were available. She believes that exploring archives can be as significant as excavating archaeological sites. Smithsonian archivist Gina Rappaport adds that there may still be undiscovered records in the NAA, indicating ongoing opportunities for new findings within their collections.