A compelling investigation into the skeletal remains of ancient Egyptian scribes from the third millennium BC has uncovered the physical toll associated with this occupation. Although the nature of their work might appear to be relatively low-stress, these individuals endured significant skeletal damage and degenerative osteoarthritis affecting various joints throughout their bodies, transforming writing into an unexpectedly painful career for many.

In a recent study published in Nature, researchers from the Czech Institute of Egyptology in Prague analyzed the skeletal remains of 69 adult males who lived in ancient Egypt between 2,700 and 2,180 BC, during the Old Kingdom period. The remains were excavated from a multigenerational elite necropolis near Abusir, close to an ancient pyramid complex.

The skeletal remains belonged to two distinct groups: scribes and non-scribes. The first group included 30 individuals, whose remains displayed noticeable anatomical anomalies absent in the control group. “Statistically significant differences between the scribes and the reference group indicated a higher prevalence of changes in the scribes, particularly osteoarthritis in various joints,” the Czech researchers noted in their article published in Scientific Reports.

“Our findings suggest that prolonged sitting in a cross-legged or kneeling position, coupled with repetitive tasks related to writing and adjusting rush pens during scribal activities, resulted in extreme strain on the jaw, neck, and shoulder regions.” This underscores the commitment of scribes to their work, as they endured considerable discomfort to fulfill their responsibilities.

The Scribes of Ancient Egypt: Custodians of Divine Words – Part I

Here’s How We Know Life in Ancient Egypt was Plagued by Disease

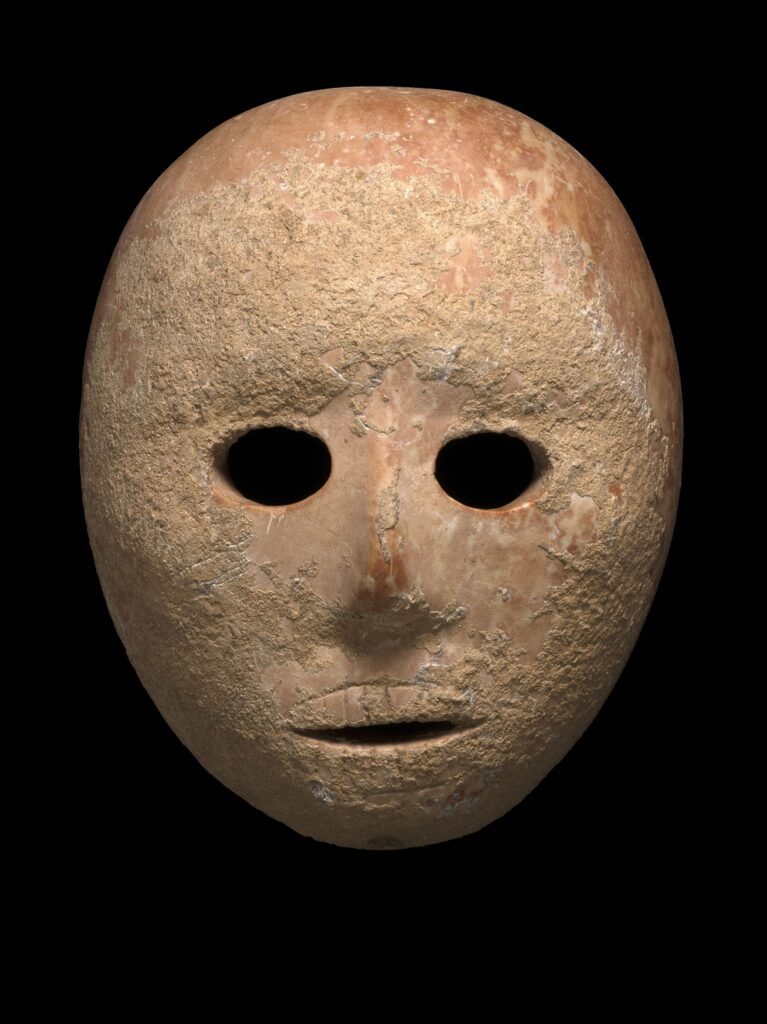

Model of the skull of Nefer—”overseer of the scribes of the crew” and “overseer of the royal document scribes.” Credit: Veronika Dulíková, Czech Institute of Egyptology; data processing and 3D model creation by Vladimír Brůna, Zdeněk Marek, Department of Geoinformatics, UJEP Most. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University.

The Ancient Egyptian scribes were a highly respected class. As the masters of writing—a craft believed to be gifted by the Egyptian god Thoth and thus considered sacred—scribes enjoyed a status akin to political or religious royalty, receiving generous salaries and various privileges.

“Officials with scribal skills were part of the elite and formed the backbone of state administration,” said Egyptologist and study co-author Veronika Dulíková to Live Science. “Their role was crucial for the effective functioning and management of the entire country.”

A Day in the Life of an Egyptian Pharaoh

The Blue Lotus: A Mesmerizing Narcotic Lily of Ancient Egypt

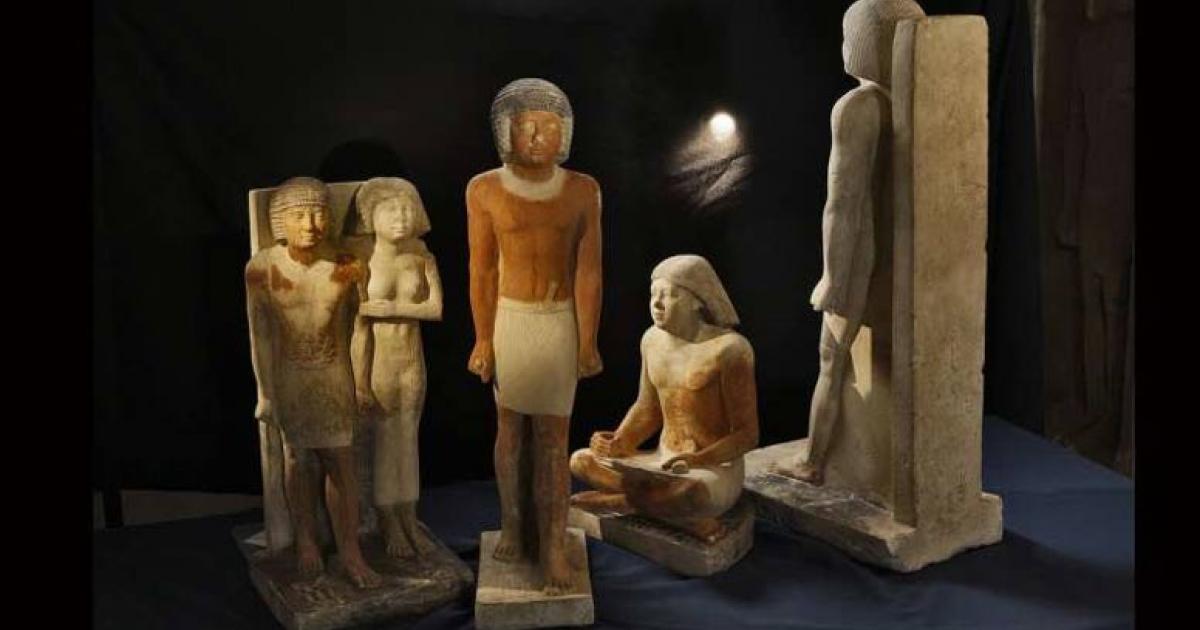

Working positions of scribes: (A) cross-legged (sartorial) position (as seen in the scribal statue of high-ranking dignitary Nefer, Abusir; photo by Martin Frouz); (B) kneeling-squatting position (wall decoration from Seneb’s mastaba); (C) standing position (also from Seneb’s mastaba); (D) varied leg positions while seated (drawing by Jolana Malátková/Nature).

Most ancient Egyptian scribes were employed by royal courts or temples and worked in various government offices. They served as official record keepers of daily life and historical chroniclers tasked with preserving the notable achievements of their leaders. The ancient Egyptians believed that documenting their deeds would ensure divine favor and prosperity, prompting scribes to be generously rewarded for their literacy and honed writing skills.

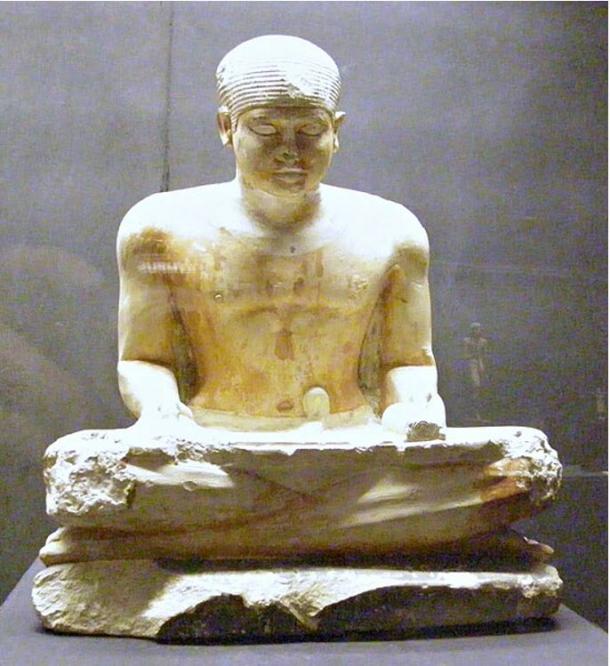

Much is already known about the lives of Egyptian scribes due to their society’s emphasis on record-keeping, which ensured their activities and identities were well-documented. Statues and wall carvings depicting scribes at work illustrate not only the significance of their role but also the high status they enjoyed.

Statue of a scribe from the 5th dynasty, housed in the Museum at Saqqara; Catalogue Generale no. 63; this statue belonged to Ptahshepses and was discovered in a Saqqara mastaba. (Harald Gaertner/CC BY-SA 3.0)

However, this new research conducted by the Czech Institute of Egyptology has taken a groundbreaking approach to understanding ancient scribes’ lives. This marks the first examination of their skeletal remains, revealing that they experienced physical stress akin to that experienced in many forms of manual labor.

Upon analyzing the remains, researchers found clear indications of degenerative joint changes consistent with osteoarthritis. The most affected areas included the jawbone, right thumb, right collarbone, right upper arm near the shoulder socket, lower end of the right thigh bone at the knee joint, and upper spine vertebrae. Additionally, they observed indentations on kneecaps and flattened areas on the lower right ankle bones.

Drawing illustrating regions of skeletal damage among scribes compared to the reference group. (Drawing by Jolana Malátková/Nature)

The damage identified suggested that scribes spent prolonged periods sitting cross-legged or kneeling on their left legs while bending their right legs to support papyrus on their laps. They also hunched over while writing—a posture reminiscent of modern office workers.

Thanks to statues and wall reliefs showcasing scribes in action, researchers could correlate specific skeletal damage with these detrimental postures. “In a typical scribe’s working position, the head had to be tilted forward, and the spine flexed, altering the center of gravity and placing stress on the spine,” explained anthropologist and lead author Petra Brukner Havelková to Live Science. “Moreover, clinical studies have documented a connection between jaw disorders and cervical spine dysfunction or neck/shoulder symptoms.”

In addition to adopting unnatural postures, scribes repeatedly chewed on rush stems used as writing tools, pinching them tightly between their thumbs and forefingers while writing—activities that likely contributed significantly to joint damage in their thumbs and jaws.

Nice Work if You Can Get It

Ultimately, it appears that life as a scribe in ancient Egypt was not as effortless as one might assume. Despite their elevated status, the work involved was monotonous and constrained to limited physical movements. Scribes maintained similar postures for hours while focusing on their writing tasks, rarely taking breaks due to pressure to complete assignments quickly.

“We realize that although they were high-ranking officials belonging to Egypt’s elite, they faced similar challenges as we do today and encountered comparable occupational risks common among many civil servants,” Havelková observed.

While they certainly paid a physical price for their high status, scribes likely had access to superior healthcare services available at that time and enjoyed luxurious lives upon retirement.