Nestled in the windswept St Kilda archipelago off the coast of Scotland, Hirta Island is a testament to human resilience. This isolated island, once home to a small but hardy community, holds a unique place in Scottish history. The story of Hirta is one of survival, adaptation, and, ultimately, an inevitable departure from the land its people had called home for over 2,000 years. Today, Hirta remains uninhabited, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that shelters a rare ecosystem, providing a glimpse into a life forged through hardship and dedication in one of the world’s most remote places.

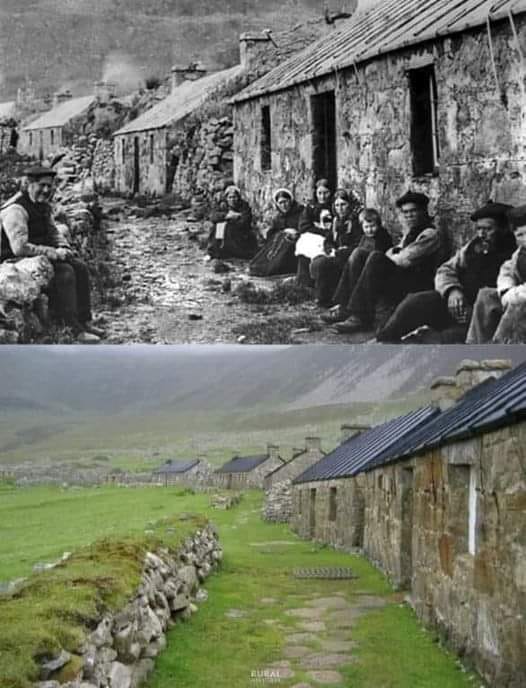

The “Main Street”: A Symbol of Resilience and Change

In 1861, a transformative event reshaped life on Hirta. The islanders constructed a row of sixteen single-story cottages, which they referred to as the “main street.” These new homes, with chimneys and slate roofs, were built in response to a devastating hurricane that had severely damaged the older blackhouses—traditional structures made from drystone walls with thatched roofs, vulnerable to the island’s fierce weather. By replacing the blackhouses with sturdier, modernized cottages, the community demonstrated its adaptability and resilience in the face of harsh conditions.

The “main street” wasn’t just a row of cottages; it was a symbol of progress and resilience. The villagers preserved traditional ways of life through crofting, a small-scale farming practice, but also found ways to modernize without abandoning their heritage. This blend of old and new showcased a community capable of holding onto its identity while evolving to meet new challenges.

A Diet Shaped by Isolation and Innovation

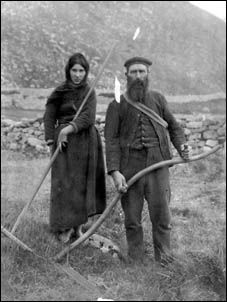

Living on Hirta was an exercise in survival and ingenuity. Due to the dangerous waters surrounding the archipelago, fishing—often a staple for island communities—was nearly impossible, leaving the villagers to rely on seabirds and their eggs as their main source of sustenance. Hunting seabirds required exceptional skill and knowledge of the rugged cliffs. Islanders gathered gannets, puffins, and fulmars, whose meat, oil, and feathers became integral to their diet and economy. This reliance on seabirds was not merely a choice but a necessity; the isolation of the island meant that the people of Hirta had to make the best use of whatever the land could provide.

The islanders’ dependence on seabirds highlights their incredible adaptation to the environment. Their diet reflected not only their ingenuity but also their close relationship with the natural world—a connection that was both nurturing and precarious. Seabird hunting techniques passed down through generations became a part of their identity, linking them to the land and sea in ways that few modern societies can fully appreciate.

The Decline of Hirta: Disease, War, and the Exodus

By the early 20th century, life on Hirta had grown increasingly precarious. Disease, introduced by visiting tourists, took a toll on the health and wellbeing of the islanders, further isolating them as they struggled with unfamiliar illnesses. The impact of World War I also rippled through the community; young men conscripted for military service left gaps in the island’s labor force, and wartime disruptions affected supplies and resources, adding strain to an already challenging lifestyle.

Between 1851 and 1930, Hirta’s population fell sharply, from 112 to just 36 inhabitants. With resources and manpower dwindling, the remaining islanders faced insurmountable challenges. On August 29, 1930, the remaining residents, exhausted and desperate, petitioned the British government to evacuate them. They left Hirta with a heavy heart, taking with them centuries of history and memories, leaving behind their homes and traditions.

This exodus represents not just the end of a community, but a poignant reminder of the fragility of human resilience when pitted against the relentless forces of nature and circumstance. The story of Hirta’s decline is emblematic of a broader phenomenon experienced by isolated communities worldwide, where outside influences and changing times disrupt the delicate balance between survival and sustainability.

Hirta Today: A UNESCO World Heritage Site and Sanctuary for Wildlife

Hirta now stands as a dual UNESCO World Heritage Site, celebrated for both its cultural and natural significance. Although its human inhabitants have long since departed, the island’s legacy endures in the unique flora and fauna that thrive in this untouched landscape. Among its most iconic residents are the Soay sheep, a rare, primitive breed believed to have been introduced to St Kilda thousands of years ago. These hardy sheep continue to graze the island’s rugged terrain, their isolation preserving them as a living link to Hirta’s ancient past.

Hirta’s cliffs and surrounding waters are also home to vast colonies of seabirds, including puffins, gannets, and fulmars. The island has become a sanctuary where wildlife flourishes in a setting largely undisturbed by human activity. This rich biodiversity adds another layer to Hirta’s story, showcasing the resilience of nature in reclaiming abandoned spaces.

Lessons from Hirta: A Story of Human Adaptability and Connection to Nature

The history of Hirta is more than just a tale of survival—it’s a reflection on human adaptability, the power of community, and the intricate relationships people forge with their environment. The islanders’ way of life, shaped by isolation and necessity, speaks to a remarkable resilience that allowed them to endure for centuries in a place most would consider inhospitable. Yet, Hirta’s ultimate abandonment reveals the limits of human endurance when confronted with forces beyond one’s control.

Hirta’s legacy remains as a reminder of the beauty and fragility of traditional ways of life, preserved in the ruins of its cottages and the wild creatures that now call the island home. In many ways, Hirta serves as a cultural and ecological time capsule, offering insights into a bygone era while providing sanctuary to species rarely seen elsewhere.

In the quiet stillness of its empty homes and in the bleats of the Soay sheep, Hirta speaks of a world where humans and nature were intricately intertwined. The island’s story invites reflection on our modern lives, reminding us that while technology and globalization have transformed our world, there are still places that echo the quiet resilience and adaptability that defined human existence for thousands of years.