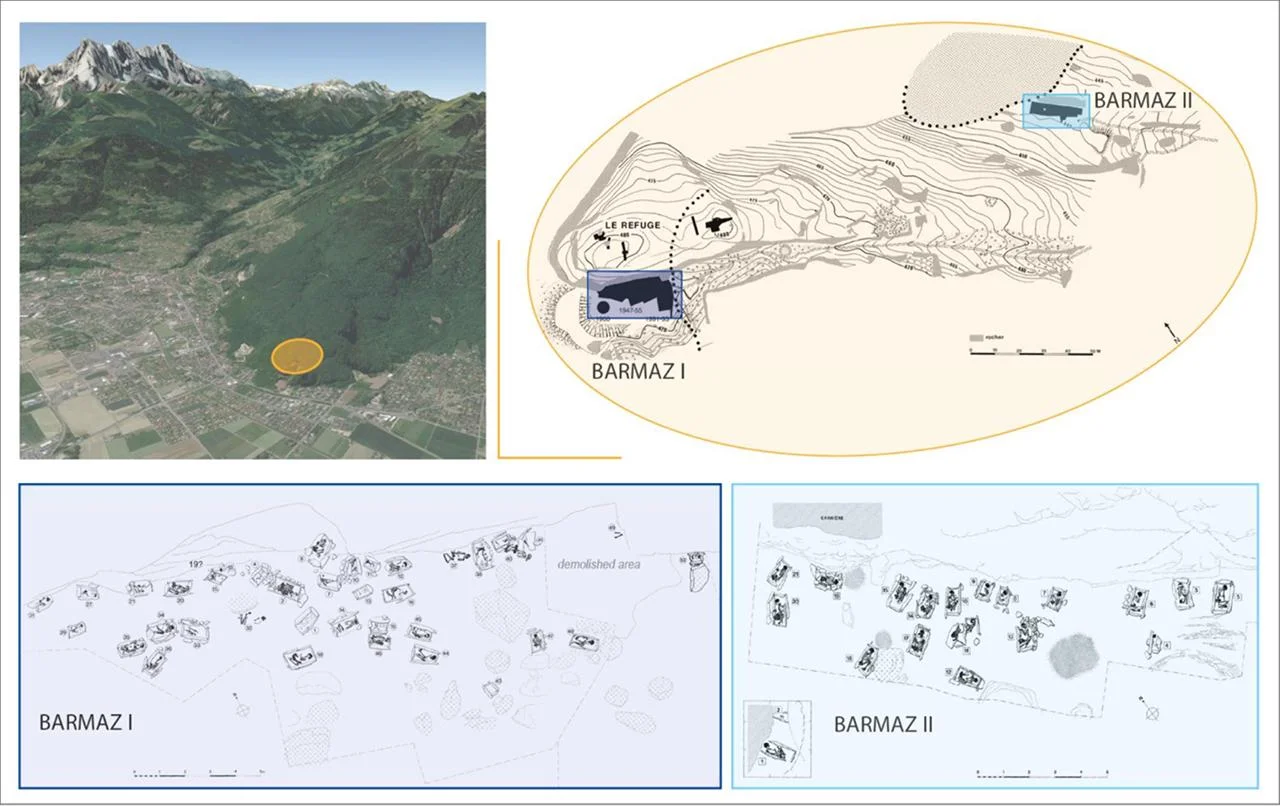

Nestled in the picturesque Swiss Alps, the Barmaz necropolis has long held the attention of archaeologists and historians alike. This Middle Neolithic burial site, dating back to between 4500 and 3800 BCE, has recently yielded fascinating new insights into the lives of its ancient inhabitants, thanks to a groundbreaking study led by Déborah Rosselet-Christ from the University of Geneva.

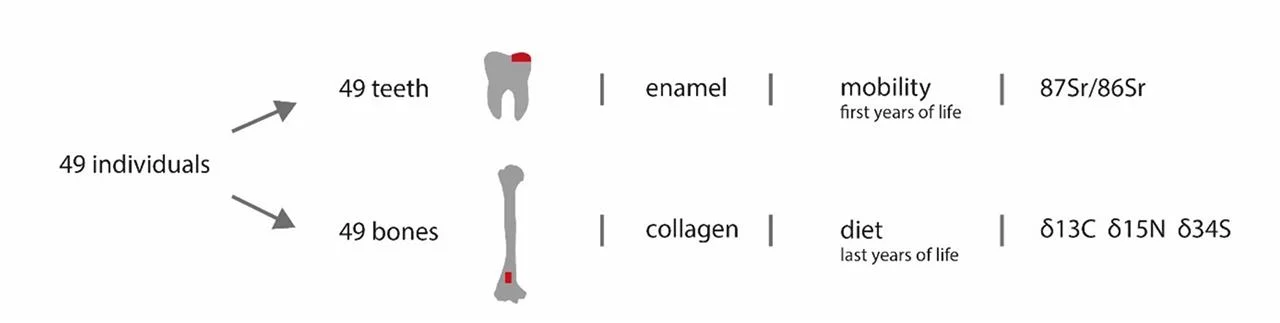

Through the analysis of stable isotopes extracted from the remains of over 70 individuals, the researchers have painted a vivid picture of the dietary habits, mobility patterns, and social structure of this early Alpine community. The findings not only shed light on the daily lives of these Neolithic people but also challenge some of the preconceptions about early European societies.

Revealing the Dietary Habits of the Barmaz Inhabitants

One of the key findings of the study was the overwhelming reliance of the Barmaz inhabitants on animal-based protein in their diet. The analysis of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the bone collagen of the individuals revealed a strong preference for terrestrial resources, particularly meat from cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs.

However, the researchers uncovered a unique aspect at the Barmaz II burial site, where some individuals showed signs of consuming a nitrogen-15 enriched resource. This could be attributed to the consumption of freshwater fish from nearby Lake Geneva and the Rhone River, or possibly the consumption of meat from unweaned young animals.

“The high consumption of animal protein, likely from cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs, was consistent across both burial sites,” explains Rosselet-Christ. “But the discovery of the nitrogen-15 enriched resource at Barmaz II was a fascinating and unexpected find, suggesting these individuals may have had access to specialized food sources or engaged in unique dietary practices.”

Tracing Mobility Patterns: Evidence of Migration and Local Roots

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study was the evidence of mobility among the individuals buried at Barmaz I. The strontium isotope analysis revealed that 14% of these individuals had spent their childhoods in different geological regions before moving to the area as adults.

In contrast, all individuals from Barmaz II had strontium isotope values consistent with the local environment, suggesting they were native to the region.

“Our results show that people were on the move at that time,” says Jocelyne Desideri, a senior lecturer at the Laboratory of Archaeology of Africa and Anthropology at UNIGE and co-author of the study. “This comes as no surprise, as several studies have highlighted the same phenomenon in other places and at other times during the Neolithic period.”

The distinction between the two burial sites raises intriguing questions about the social structure and origins of the Barmaz communities. Were the mobile individuals from Barmaz I part of a specialized group, such as traders or artisans, who had established connections with other regions? Or were they simply members of a more nomadic population who had settled in the area?

Egalitarian Society or Social Distinctions?

Despite the differences in origin, the study found no evidence of dietary inequality among the Barmaz inhabitants. Both local and non-local individuals, regardless of gender, had equal access to food resources, suggesting a relatively egalitarian society.

This finding contrasts with some other Neolithic populations, such as those in southern France, where dietary differences between sexes have been observed.

However, the researchers did uncover potential social distinctions between the two burial sites. Individuals at Barmaz II, who showed higher levels of the nitrogen isotope, might have belonged to a socially distinct group engaged in specialized activities. This hypothesis is supported by paleopathological studies indicating a higher rate of injury among individuals buried at Barmaz II.

“Despite these differences in origin, the study found no evidence of dietary inequality,” says Rosselet-Christ. “This suggests a relatively egalitarian society, which is an intriguing contrast to what we’ve seen in other Neolithic populations.”

Continuing the Exploration of the Neolithic Alpine World

The Barmaz study not only provides the first isotopic data linking diet and mobility for the Neolithic of western Switzerland but also lays the groundwork for further research. Rosselet-Christ is continuing her work as part of her doctoral thesis, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation’s ALP project, with the aim of including other sites in Valais and the Val d’Aosta in Italy.

By expanding the geographical and temporal scope of the research, the team hopes to gain a deeper understanding of the social, economic, and cultural dynamics of these early Alpine societies. The use of additional isotopes, such as neodymium, may also shed light on other aspects of their lives, such as the procurement of raw materials and the exchange of goods.

Conclusion

The Barmaz necropolis has proven to be a treasure trove of information, offering a unique window into the lives of Neolithic inhabitants of the Swiss Alps. Through the groundbreaking work of Déborah Rosselet-Christ and her team, we now have a more nuanced understanding of the dietary habits, mobility patterns, and social structure of this early Alpine community.

The findings challenge some of the preconceptions about Neolithic societies, highlighting the diversity and complexity of these early human settlements. As the research continues, the Barmaz necropolis promises to reveal even more secrets about the lives and lifeways of our Neolithic ancestors, deepening our appreciation for the rich tapestry of human history.