As reported by The Siberian Times, a group of Russian researchers has successfully analyzed the contents of a head-shaped sculpture created by the Tagar Culture over 2,000 years ago, marking a significant milestone after more than fifty years of inquiry. The findings were not unexpected.

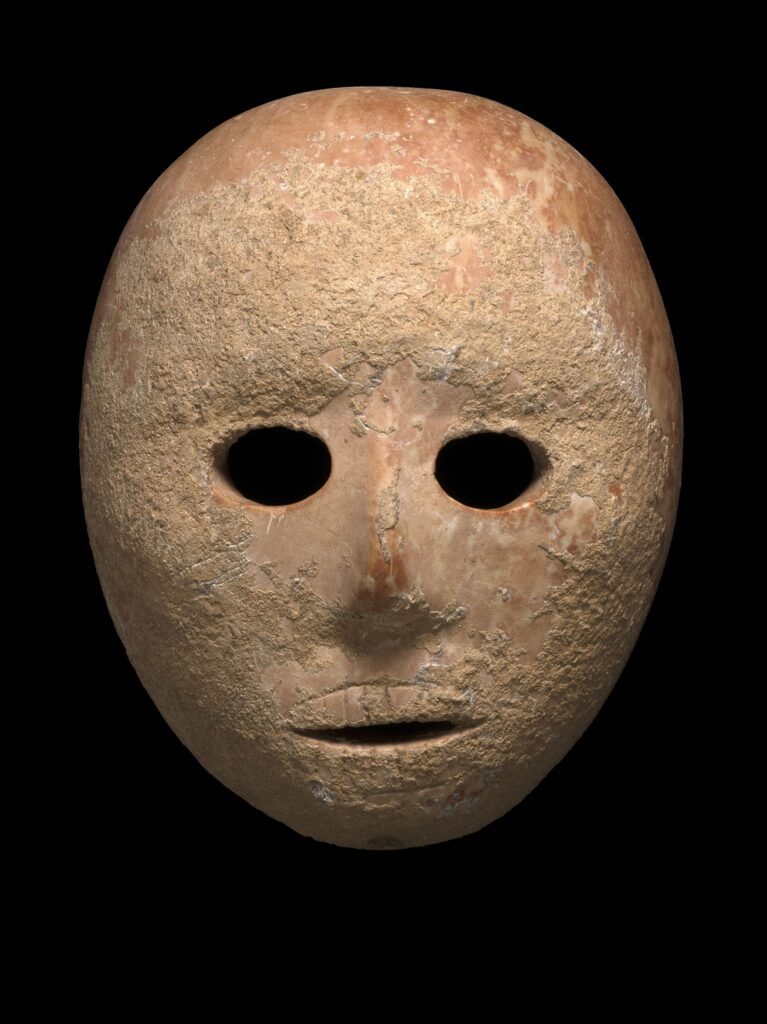

In 1968, a striking male clay funerary mask was uncovered in Khakassia, Russia, found within a communal burial site beneath a mound at the Shestakovsky cemetery. This artifact, dating back approximately 2,100 years, is attributed to the Siberian Tagar culture of the Bronze Age and concealed a genuine mystery that has only recently been unraveled.

The Tagar Culture

The Tagar people were part of the Scythian tribes that resided in southwestern Siberia from the 8th to the 2nd centuries BC. They were renowned for their livestock herding and exceptional bronze craftsmanship, leaving behind distinctive large burial mounds across the landscape.

Evolution of Funeral Practices

The funeral traditions of the Tagar culture underwent significant changes over time. Initially, these mounds served as sites for prestigious burials within chamber tombs. However, by the 5th century BC, the mounds expanded in size, leading to the replacement of chamber tombs with larger pits designed to accommodate multiple interments.

The Enigma of the Clay Mask

The clay heads that have been found belong to the later phase of Tagar culture known as the Tesinsky stage. Remains discovered in the crypts from this era exhibited signs of attempted mummification. One particular clay mask piqued the interest of Russian archaeologists when X-ray scans revealed an anomaly within it—bones were detected inside the clay head, but their dimensions did not match those of a human skull.

Revealing the Secret

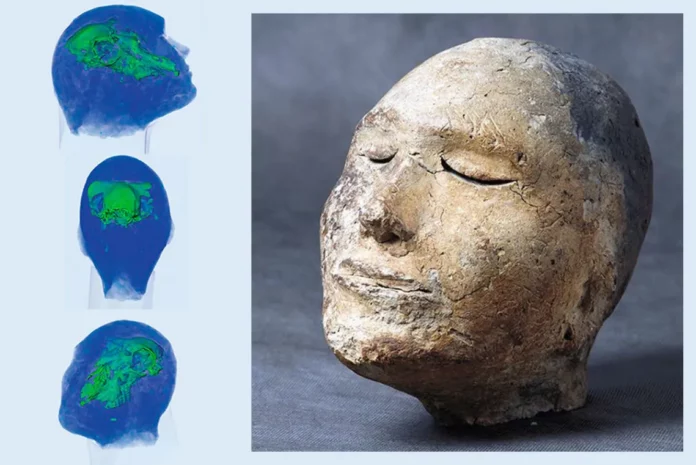

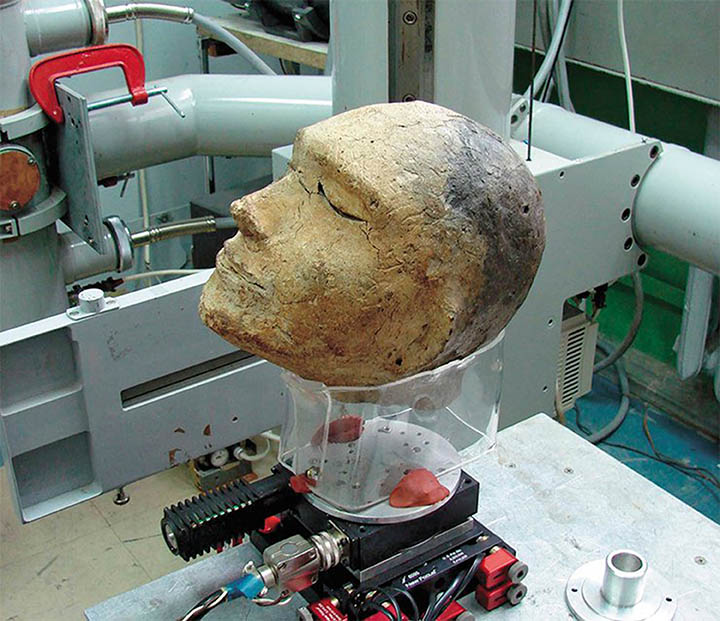

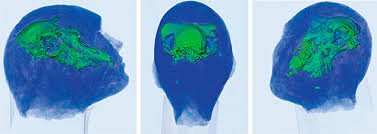

To maintain the integrity of the clay artifact, researchers opted against physically opening it. Thanks to advancements in technology, they recently utilized fluoroscopy to investigate the concealed contents of the mask.

Understanding Fluoroscopy

Fluoroscopy is a radiological method that provides real-time imaging of internal structures. By employing X-rays and a fluorescent screen, it captures images based on the attenuated X-rays that pass through an object. This technique allows for a visualization of internal anatomy.

The Discovery

The fluoroscopic examination unveiled that the clay mask contained the skull of a sheep. This marks the first instance of a non-human skull being discovered within a Tagar clay funerary mask, prompting inquiries into the implications of using a ram’s head instead of human remains.

Theories

Professor Natalya Polosmak put forth two theories to elucidate this practice. One possibility is that the Tagar people buried individuals who were never recovered, substituting them with animal remains to facilitate their passage into the afterlife. Alternatively, utilizing animal remains might symbolize a fresh start or a new status for the deceased.

Complex Burial Customs

Dr. Elga Vadetsakaya proposed a third theory based on her research into burial customs during the Tesinsk period. She theorized that these clay heads were part of a two-step burial process that involved initial partial mummification followed by interment in a large pit. The clay heads served as representations of the deceased, enabling families to recreate their likenesses if the original remains had decomposed or been harmed.

Conclusion

The discovery of a sheep’s skull within the Tagar clay mask provides valuable insights into the burial customs and beliefs of the Tagar culture. While the precise reasons for incorporating animal remains remain ambiguous, ongoing research and advancements in technology may illuminate further details about this fascinating artifact.

We invite you to share your thoughts on the Tagar culture and the theories discussed. Your perspective is highly valued!