Introduction: The Giant of the Appalachians

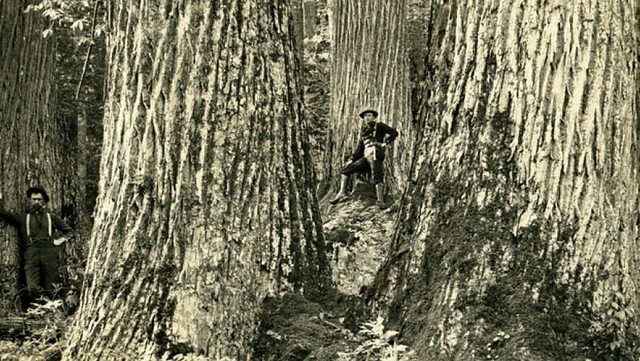

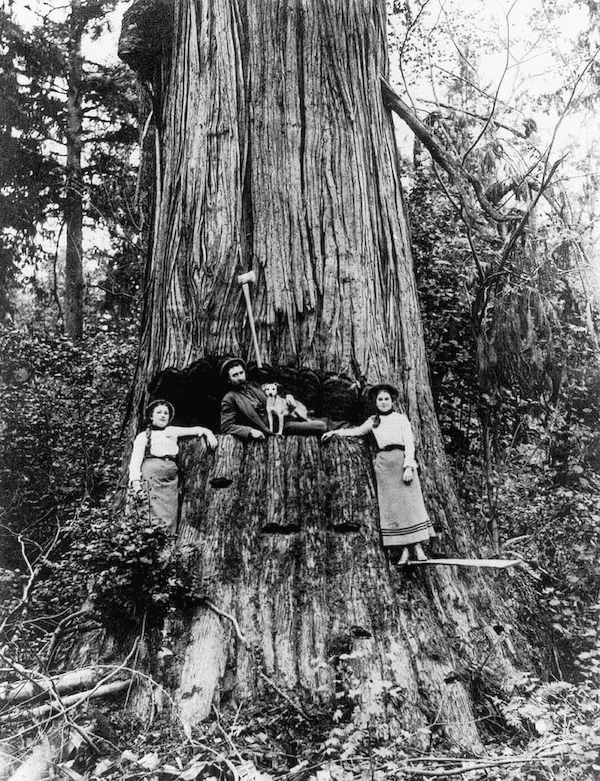

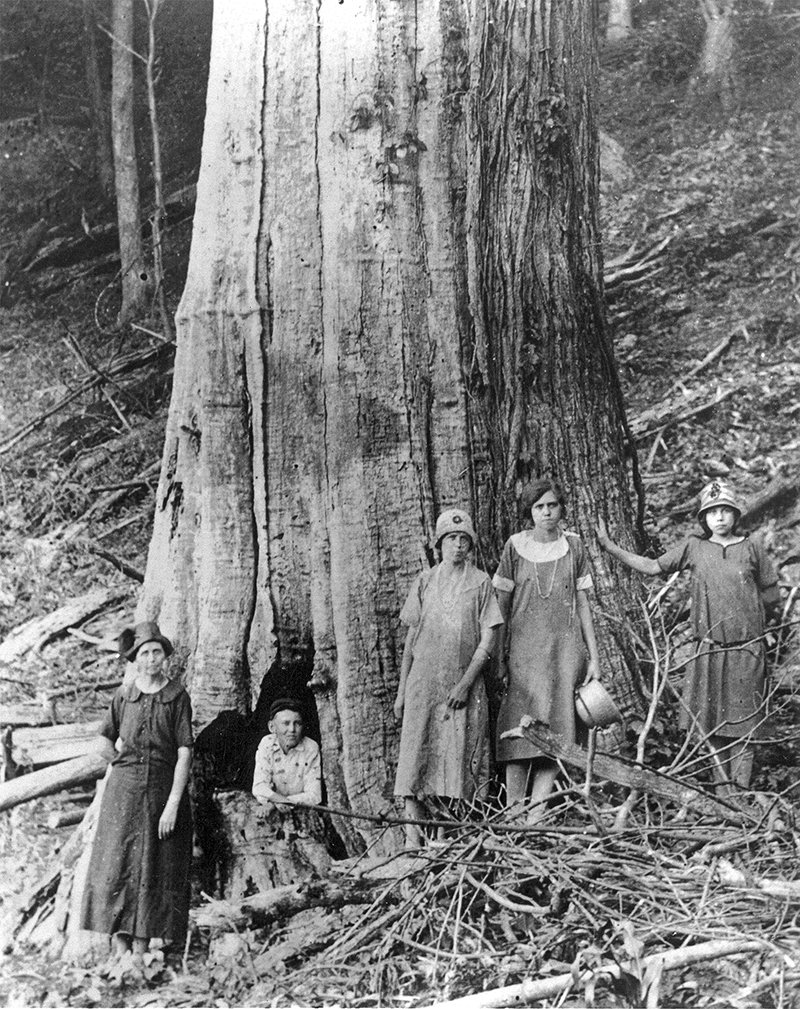

The American chestnut tree (Castanea dentata) once reigned supreme over the forests of the Appalachian region, accounting for nearly 25% of the hardwood canopy. Towering over 100 feet tall and capable of living for centuries, these trees were not just majestic but were essential to both wildlife and human life. Their nuts served as an abundant food source for animals like deer and bears, while their durable, rot-resistant wood became a vital resource for building homes, furniture, and fencing. However, this giant’s dominance was brought to a tragic end by a blight that devastated the species in the early 20th century.

The American Chestnut’s Role in Ecosystem and Economy

The American chestnut was a cornerstone species in the Eastern forests. It supported the entire ecosystem by providing reliable food for wildlife, and its ability to produce large quantities of nuts each year made it invaluable to both rural families and commercial sellers. Families would gather these nuts during the fall, often selling them at local markets, which contributed to the local economy. Beyond its economic benefits, the wood of the chestnut tree was prized for its strength and resistance to rot, making it ideal for construction.

The Blight: A Catastrophic Event

In 1904, a fungus known as Cryphonectria parasitica was accidentally introduced to North America through imported Asian chestnut trees. Unlike its Asian counterpart, the American chestnut had no natural resistance to the blight. Within a few decades, the blight spread across the entire range of the chestnut, killing an estimated 4 billion trees by the 1950s. This ecological disaster fundamentally changed the landscape of the Appalachian forests, eliminating not only a species but also disrupting the food chains and ecosystems that depended on it.

Ecological and Cultural Impact

The loss of the American chestnut tree had far-reaching consequences. Wildlife that relied on the chestnuts for food saw their populations decrease or their habits change, affecting biodiversity in these forests. Culturally, the tree’s disappearance was equally impactful. For centuries, communities in Appalachia had relied on chestnuts as an integral part of their food system, local economy, and way of life. Festivals and traditions centered around the chestnut harvest became a thing of the past, leaving a gap in both the landscape and the culture.

Restoration Efforts: A Ray of Hope

In recent years, scientists and conservationists have been working to restore the American chestnut to its former glory. Breeding programs have aimed to develop blight-resistant trees by crossing American chestnuts with their Asian relatives. While this has produced some promising results, the hybrids still do not possess the full stature and characteristics of the original American chestnut.

One of the most exciting developments is the use of genetic modification. By introducing a gene from wheat that can neutralize the blight fungus, scientists have created transgenic American chestnuts that show strong resistance to the blight. These trees are undergoing trials, and if approved, they could be reintroduced into the wild.

A Symbol of Ecological Recovery

The potential restoration of the American chestnut is about more than just one tree—it represents the possibility of healing ecosystems and correcting past environmental mistakes. While there is still much work to be done, the efforts to bring this iconic species back to its native habitat could pave the way for other large-scale restoration projects, signaling a brighter future for biodiversity and conservation.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Legacy

The American chestnut tree, once known as the “redwood of the East,” was not just a tree but a symbol of resilience and abundance in the Appalachian forests. While its near-extinction was a catastrophic blow to both nature and human communities, modern efforts to revive this giant show that recovery is possible. If successful, the return of the American chestnut would be one of the greatest triumphs in conservation history, proving that nature, with a little help from science, can reclaim its place in the world.