The “Man in the Golden Dress,” unearthed during archaeological excavations in 1969-1970 at the Issyk (Esik) Kurgan near Issyk Kul, Kazakhstan, is one of the most extraordinary finds of the 20th century. Dating back to the 5th century BC, this burial mound—commonly referred to as a kurgan—offers profound insights into early Turkic and Scythian culture. It provides a rare glimpse into their burial practices, societal hierarchies, and artistic craftsmanship, representing a landmark in the study of ancient Central Asian civilizations.

The Discovery of Tigin: A Royal Heir

The individual buried in the kurgan, identified through radiocarbon dating as a young male between 17-18 years old, is believed to have held the title Tigin or Tegin, a designation given to the heir of a khan in ancient Turkic societies. His age, combined with the richness of the burial, suggests that he was a person of significant status, possibly a prince or a future ruler. The tomb’s opulent nature—filled with intricate golden attire, ceremonial armor, and other lavish treasures—reflects the high societal rank of the young heir and the great care taken in honoring him in death.

The tomb itself is not just a resting place but a reflection of the elaborate funerary customs of the time. The large kurgan, constructed with remarkable architectural skill, highlights the advanced construction techniques used by early Iron Age and Bronze Age civilizations in Central Asia. This reveals much about the societal hierarchy, wealth, and reverence for royalty, emphasizing the grandeur with which noble individuals were buried.

The Golden Armor: A Symbol of Wealth and Power

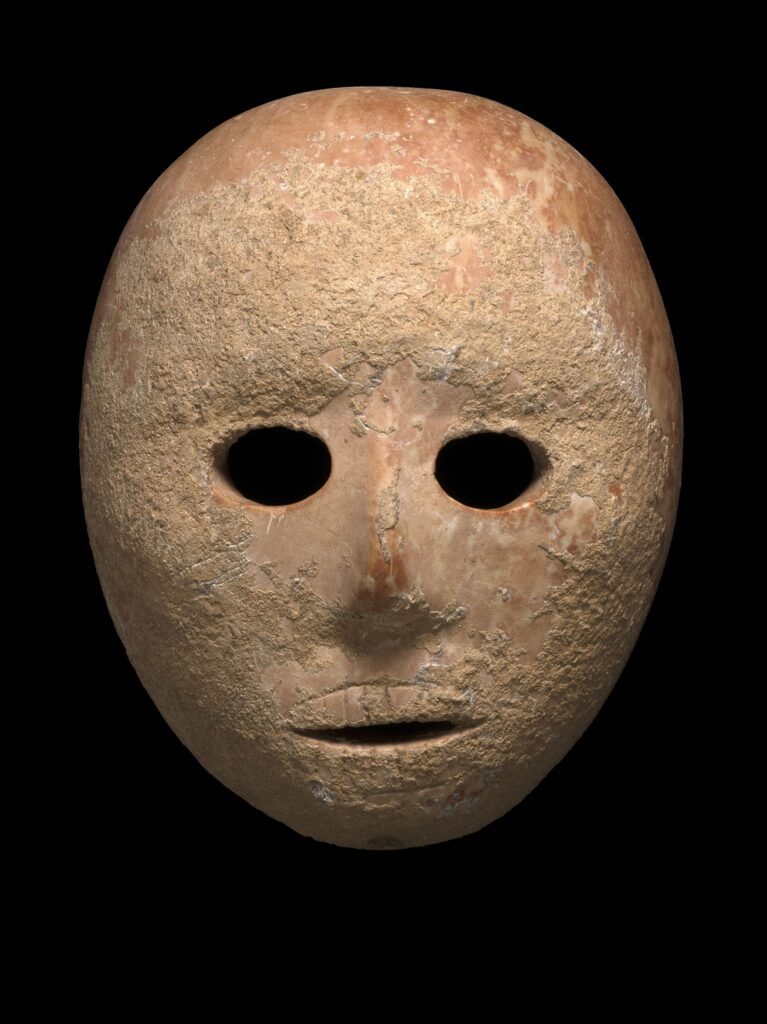

The “Man in the Golden Dress” earned his moniker due to the magnificent gold armor in which he was laid to rest. This striking attire was adorned with elaborately crafted ornaments and patterns, showcasing the exceptional artistic abilities of the Scythians and ancient Turkic tribes. The gold decorations include depictions of mythological figures and animals, pointing to the deep spiritual and symbolic significance of these motifs in the culture.

The gold armor served not only as a marker of the individual’s wealth but also as a possible protective measure in the afterlife, symbolizing power, protection, and divine favor. The intricate craftsmanship of the gold work demonstrates the high level of technical skill achieved by these early societies and sheds light on their cultural values and beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife.

The Silver Vessel and Proto-Turkic Writing: A Linguistic Breakthrough

One of the most remarkable discoveries within the Issyk Kurgan was a silver vessel engraved with one of the oldest known examples of Proto-Turkic writing. The inscription, which reads “Han Uya” (“Tigin died on the 23rd. My condolences to the people of Esik”), is an extraordinary linguistic artifact, dating back to the 5th century BC—nearly 1,000 years older than the renowned Orkhon Monuments, which were previously thought to be the earliest examples of Turkic script.

This inscription is not only significant for its age but also for what it reveals about the early development of written language among the Turkic peoples and their neighbors, such as the Scythians. It suggests that these ancient societies had developed advanced methods of communication and record-keeping, further underscoring the complexity and intellectual sophistication of their culture.

The silver vessel also hints at the ceremonial practices associated with burials, perhaps used in a rite or offering related to the young prince’s passing. It represents a tangible connection to the ancient peoples’ understanding of life, death, and the sacred, marking a pivotal moment in the study of Proto-Turkic linguistics and early written communication in Central Asia.

Cultural and Historical Significance

The discovery of the “Man in the Golden Dress” has revolutionized the understanding of early Turkic civilization and its interactions with neighboring cultures, such as the Scythians. The lavish nature of the burial, combined with the presence of advanced writing, points to a society deeply connected to both material wealth and intellectual achievement. The fact that this burial occurred in the 5th century BC positions it at the crossroads of key cultural exchanges in Central Asia, a region known for its role as a hub of trade and communication along the Silk Road.

Moreover, the kurgan offers scholars critical insights into the spiritual and social practices of early nomadic tribes in Central Asia. The objects discovered within the tomb, from the golden attire to the engraved silver vessel, are part of a larger narrative about the importance of ritual, status, and artistic expression in these ancient cultures.

Conclusion: A Testament to Early Turkic Ingenuity

In conclusion, the “Man in the Golden Dress” is far more than an archaeological curiosity—it is a crucial piece of the puzzle in understanding the evolution of early Turkic and Scythian cultures. The richness of the burial site, the artistic achievements demonstrated by the golden armor, and the profound linguistic significance of the Proto-Turkic inscription all highlight the ingenuity and cultural sophistication of these ancient peoples.

As one of the most significant archaeological finds in Central Asia, this discovery reshapes the historical understanding of early Turkic civilization and its place in the broader context of ancient world history. It continues to inspire fascination and scholarly inquiry, offering a window into a world that was, until recently, shrouded in mystery.