Archaeology continues to reveal intriguing insights into the medical practices and rituals of ancient societies. A recent find in Crimea exemplifies this, as researchers have discovered the skull of a man who lived 5,000 years ago and underwent a failed brain surgery.

The Extraordinary Find

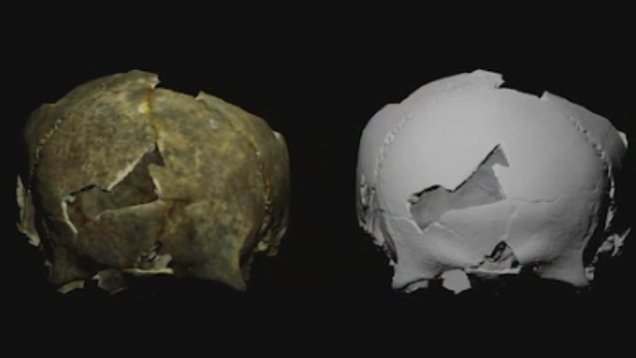

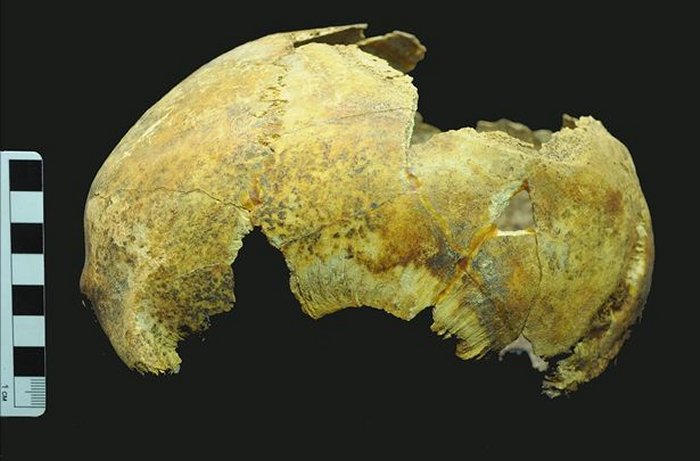

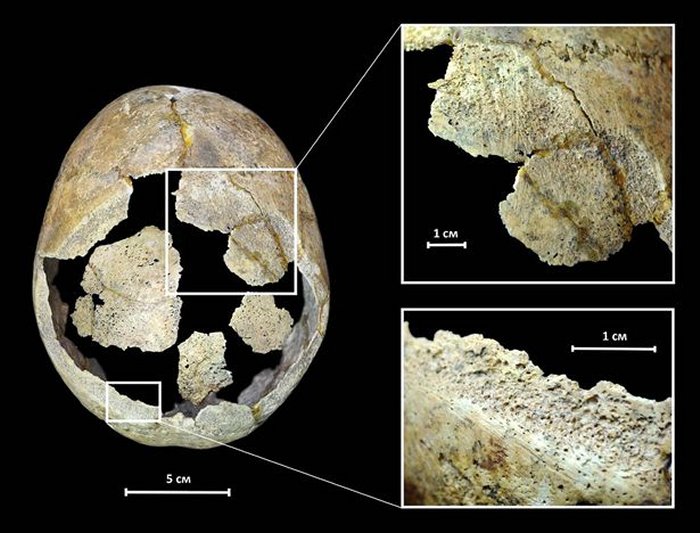

Archaeologists have uncovered the skull of a Bronze Age man in his twenties who experienced trepanation, an ancient surgical technique involving the creation of an opening in the skull. Advanced 3-D imaging and photographs from Crimea reveal signs of this procedure. Scientists indicate that the surgery was unsuccessful, and the unfortunate patient likely survived only a short time following the intervention with a stone ‘scalpel.’ According to the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, “the ancient ‘doctor’ certainly utilized a set of stone tools for surgery.”

The positioning of the bones suggests that the deceased was intentionally and thoughtfully arranged. The skeleton was found lying on its back, slightly tilted to the left, with the knees bent sharply and angled toward that side.

Burial Artifacts

In addition to the skeletal remains, archaeologists found large pieces of red pigment situated near the head, covering the top of the skull. Two flint arrowheads were also interred alongside the ancient individual.

This careful burial method, coupled with the presence of symbolic artifacts, implies that this person held an important status within their Scythian community. The deliberate arrangement of the body and the use of red pigment likely formed part of the cultural burial rituals practiced during that era.

Insights into Ancient Medical Practices

The dimensions of the trepanation were measured at 140 × 125 millimeters. Dr. Maria Dobrovolskaya, head of the Laboratory of Contextual Anthropology, remarked, “This young man faced misfortune. Although survival rates after trepanation were generally high in ancient times, he seemingly died soon after the operation.”

Olesya Uspenskaya, a researcher specializing in Stone Age archaeology, noted that three distinct types of marks were made by prehistoric ‘surgeons’ using various stone blades. These included small long linear tracks, larger deep linear grooves formed in parallel, and marks created with a thicker blade.

Experts believe that trepanation was performed in ancient times for both surgical and ritualistic reasons. The objectives of such brain surgeries could have included alleviating severe headaches, treating hematomas, repairing skull injuries, or addressing epilepsy. This remarkable discovery provides valuable insights into the medical knowledge and practices of our ancient predecessors.